Sigma Q&A: Why the 24-70 DG DN is *such* a good deal, why FLD glass is tricky, and (much) more…

posted Wednesday, September 16, 2020 at 2:52 PM EDT

This is the fourth and final interview of a series I conducted while in Japan in early March of this year, a trip I barely managed to sneak in before the Coronavirus travel restrictions. (Here are links for my other interviews with Olympus, Panasonic and Fujifilm from that trip.) Between the COVID situation, the sale of IR, and a number of other lingering content projects I needed to finish, I'm only just now managing to post it and the others.

This time, I'm interviewing Mr. Kazuto Yamaki, the CEO and driving force behind Sigma, the world's foremost third-party lens manufacturer. Yamaki-san is one of the most interesting industry executives to interview, for a couple of reasons. First, he's the ultimate authority within the Sigma organization, so he can speak much more freely than can executives at other companies, who often have to be careful about toeing a corporate line in terms of what they talk about and how they frame their answers. Secondly and possibly even more importantly, Mr. Yamaki is unusually involved with Sigma's engineering, product development and manufacturing on a personal level, so he's able to discuss their products at a fairly deep technical level. The bottom line is I always come away from my conversations with him with new insights and loads of relevant information. This time was no exception :-)

As everyone knows, the world has changed drastically in the six months since my visit, so my questions about the projected impact of COVID on Sigma's production capacity from back then are completely out of date. I reached out to Mr. Yamaka for an update before posting this story, and took the opportunity to also discuss some of Sigma's latest lenses that have been announced in the intervening time. These include some pretty amazing optics, so there's lots of new material, and the combination of the old and the new makes this possibly my longest interview to date. (Over 12,000 words :-0) I hope you'll find it as fascinating to read as I did to have the original conversations!

Without further ado, here's what we talked about, beginning with followup questions asked in early September, 2020, about COVID impact. (The parts below that came from my recent conversation with Yamaki-san are identified by the "Followup" subheads.)

Followup: COVID impact

DE: It’s good to be able to chat again, how are things going for Sigma currently?

KY: It was tough earlier, but right now we are doing OK.

DE: I’d heard some stats (second-hand) from a US market research firm, that said that the market was hit very hard, but that lens sales weren’t as bad as those for camera bodies.

KY: Seriously?

DE: Yeah

KY: According to the statistics from CIPA, and from global market research, I don’t see such a trend. Most camera bodies and lenses are all down compared to last year. Lenses are not an exceptional case.

DE: Ah, that’s too bad, but things are still going OK for you?

KY: Yes, we suffered a lot in April and May, but sales have come back since June. Interestingly, even in the tough time during April and May, some lenses stayed popular.

DE: Oh really?

KY: I mean the macro lenses; actually the demand for macro lenses instantly increased a lot.

DE: Yeah, I can imagine, everyone was at home, that makes sense.

KY: Yes, they have to enjoy photography at home or at gardens, and with stationary objects.

DE: Very interesting, that makes sense. But now it’s back more broadly, other lenses are selling as well? You’ve had so many remarkable new lens announcements, I’d imagine those are doing very well, neh?

KY: Thank you very much. They are well accepted almost all over the world. The market situation is not consistent across the world, though. Some countries are very good, but some countries are still suffering.

DE: Yeah, the US is still having very big problems with COVID, but for instance Sweden took a very different approach to the disease early on to the, and it seems like they’re doing quite well now.

KY: Yes, it’s really surprising actually.

DE: Is Sweden one of the countries that is seeing better sales for you, or do you not have the data at that level, but rather just for the EU?

KY: Yes, yeah, it’s surprising. [Ed. note: I’m not sure if he means Sweden is doing well, or that yes, he only has EU data.]

DE: And Japan itself has done quite well with the virus. I know there’s been some concern lately, because cases have gone up some, but overall you’ve done much better than the US. It seems the Japanese government is being concerned about perhaps 1,000 new cases per day, but here in the US just my own state of Georgia is still seeing levels more than twice that, and we only have about 10 million people. (The whole state of Georgia is only about ¼ the size of just the Tokyo Metro area alone.) There’s some thinking that the tests may be too sensitive, that then can pick up just fragments of virus (not even whole viruses), so we may be overreporting. The good news, though, is that fatality rates in the US are much lower than they were in the early days. Of course, the big problem is I don’t get to come to Japan. <both chuckle>

We talked some about COVID back in March, but that was six months ago and it was a different world then, so I wanted to follow up, to see how it is going with your suppliers, your own production, that sort of thing.

KY: First of all, our production system has not been affected by COVID-19, almost at all. Some parts we purchase from Japanese companies, but they have factories in China. They had some minor problems in delivering those parts to us, but it did not affect our production. Right now, we have no problem at all.

DE: Oh, that’s great! As I said, Japan has relatively little problems, but even more so Aizu is so separate, that I think that only now are you starting to have just one or two cases up there, neh? [Ed. note: Aizuwakamatsu in the Fukushima prefecture is where Sigma’s factory is located.]

KY: Yeah, very few cases.

DE: I remember that at the time, we were also talking about your engineering staff, that they couldn’t really work at home because they needed access to the CAD systems, and there would have been security issues with letting those systems go off-site. It sounds like it hasn’t been a problem, though. I think Tokyo for a while had a work from home order, or was that just a recommendation?

KY: It was a recommendation, it wasn’t mandatory, but we followed that advice, and in April and May, we only allowed 30% of our employees to come to the office, and the rest of the staff worked from home. We lifted that restriction in June; in June we allowed 50% of the employees to work at home. From the beginning of July, we let everyone back into the office, 100%, but in the middle of July, the virus cases [in Japan] suddenly increased a lot. So everyone was back in the office for two weeks, but since mid-July, we allow 30% to work from home, and we are still continuing that arrangement.

DE: I would imagine you could skew it a little bit, and have more engineers in the office, while more of the administrative staff work from home, right?

KY: Yes, that’s true; we prioritize the engineers, especially those who are working on urgent projects. All the staff like sales, marketing, other administration, we ask them to stay and work from home. But as you know, most of the employees at our headquarters are engineers, maybe 80%.

DE: Oh wow, I had no idea it was that many!

KY: Yeah, maybe 75-80%, so it was still challenging.

[The following are questions from the original interview in March, 2020.]

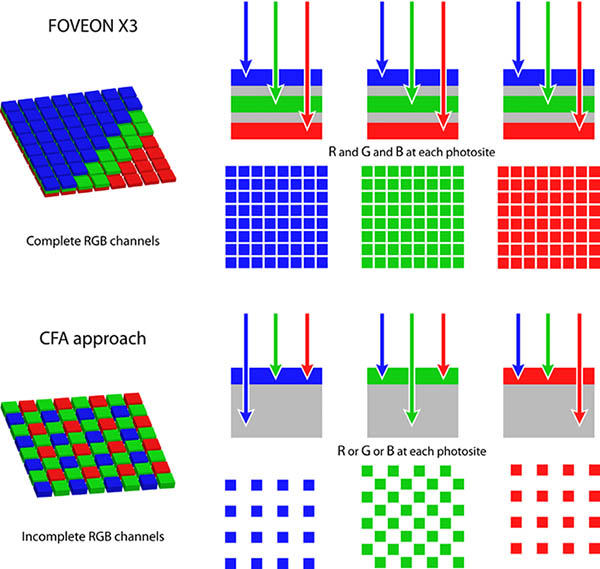

DE: Turning to products, I was very sad to see recently that you had to step back from plans for the full-frame Foveon. That must have been a very difficult decision. What can you tell us about that, and what do you see as the future for the Foveon technology?

KY: We're still working on the Foveon technology, and we're still working on the full-frame sensor. We had a plan to release the product, the camera with the full-frame Foveon sensor in 2020, but we found it impossible. So we continue the development of the sensor, but we cannot commit [to] when we will release the product.

DE: Right, right.

KY: So the step back means we first focus on the development of the Foveon technology. Then once the sensor is ready, we will release the camera.

DE: So you're basically just having to do fundamental work on Foveon technology.

KY: There are two issues. The first one is there are some design errors in making the full-frame Foveon sensor. We already have several generations of the full-frame Foveon sensor prototypes. But none of them work properly because of the design error. So we have to correct the design error. The Second problem is a challenge in manufacturing.

DE: Mmm!

KY: Starting from this project, we started working with a new sensor vendor.

DE: Oh, I see, a new foundry, or...

KY: Yes, a new foundry in the US. They are based in a small city called Roseville (California), which is close to San Francisco. They were the subsidiary of NEC, a Japanese company.

[Ed. Note: Some quick Googling suggests this is TF Semiconductor Solutions, previously TSI Semiconductors (2012-2014), and Renesas Electronics America (2010-2011). As Yamaki-san says, the foundry was originally built in 1998 by NEC. Please note, though, that this is just my guessing, based on a Google search :-)]

DE: Oh, really? Ah.

KY: Do you know kaizen, the continuous improvement philosophy/ They apply kaizen principles in their factory, so their quality is quite high.

DE: Mmm, mmm.

KY: And also, they can work very closely with Foveon, because it's located in the same area. So same time zone, and same language; I thought it's good idea to have them work together on this project. But it was quite challenging and time-consuming to transfer the Foveon sensor manufacturing technology from the current [foundry] to the new one. It's a bit more challenging than I thought.

DE: Yeah, because it would be a very different semiconductor process than most chips, just with the different layers, and how you have to do the doping and things...

KY: Yes. I heard it's not totally different, but it's different, so it's challenging. And also for them, it's the first time to make full-frame.

DE: Oh, full-frame. Oh, they have to splice the two pieces together.

KY: Yes.

DE: I could never figure how they can do that. It's amazing to me that they can get it right down the middle of the pixels, you know?

KY: Actually, [although] the technology is called stitching, they do not physically stitch two physical sensors together. They expose the two times [during the photolithography process].

DE: Oh, I see!

KY: So, using a stepper, they have to perform two exposures exactly, with a very, very high precision so that they are perfectly aligned between exposures.

DE: Ah, that makes more sense to me. Because someone had told me that they were physically separate chips, and I thought there's no way to do that mechanically. So this is the first time that company has done double-stepping.

KY: Yes.

Sigma fp success

DE: On a more positive note, we're very excited that we're finally about to get our sample of the Sigma fp. The guys at the office are very, very excited about that. Where are you at in terms of shipping that?

KY: We started shipping that camera at the end of October.

DE: Oh, really, that long ago? I guess it just took a while for us to get one. I think there was uncertainty about what was happening with IR maybe, so that may have delayed us getting a sample. How is it being received by the market? Are the sales what you expected, or above / below your projections?

KY: We are doing extremely good in Japan. The sales here are quite good. But in other markets, sales are not as good as I expected.

[Ed. Note: IR has since had the chance to test a sample of the fp, for all the details, check out our Sigma fp review (including two videos).]

DE: Is Japan better than you expected, or what you expected?

KY: The initial sales were better than I expected. Right now, it's on track. I think in other markets, not so many potential users tried our camera. So we will probably have more touch-and-try events, so that many customers can try [the fp for themselves].

[Ed. Note: Obviously not an option right now in most countries, due to the Coronavirus crisis.]

DE: From the sound of it, in Japan there were more people already familiar with Sigma cameras.

KY: Yes. And if you go to some major camera stores like Yodobashi or Bic Camera or Kitamura, most of the camera stores have demo samples there.

DE: Ah, that's good. So my impression was really that the biggest focus of the fp is in video applications. Is that a fair statement, or is it equally still [and video], really?

KY: No, for me [it's] 50/50, still and video. When I talk about the technology in it, if you switch the mode then you can see the user interface is completely different. Normally, cameras with a video function have the same user interface, regardless if it's movie or still. There are some more menus on the screen, but basically, it looks the same. But we developed a completely different user interface for still and video, and spent about the same time [for each]. So when it comes to the technology in it, I would say it's quite equal. The still and video are equally positioned. But still, our main target customers are still photographers.

DE: Really? Mmm.

KY: Yes. With the fp.

DE: Ah, that's interesting.

KY: Especially those who like street photography.

DE: Ah, because it's so small, so tiny.

KY: It's good for those who don't like to carry big cameras, like big DSLRs. So I hope many still photographers will try our fp. I think that's the biggest difference between Japan and other markets. Like you said, other markets regard this camera's main feature as video. But in Japan, I can't say the number but most of the users are still photographers.

DE: Really?

KY: Yes. They take still pictures, with fp.

DE: That's interesting.

KY: And as you know, the still photography market is much bigger than the video market.

DE: Ah, that was going to be one of my questions, how big the markets are. So still continues to be much bigger than video.

KY: Yeah, well ahead. For video, video shooters with big sensors are typically professionals: Videographer, filmmakers or cinematographers. They are a very small market.

DE: Interesting. I guess it stuck out in my mind so much because from the event, I remember seeing all these video rigs with big lenses and the frame and everything, and that stuck in my mind a lot. Of course, at IR we're much more still people, so that will be more the focus of our own coverage of it.

KY: In Japan, many customers enjoy the fp with Leica M-mount lenses. They use the Leica M-to-L adapter, and then they attach the very classical, compact Leica lens.

DE: Oh, that's interesting!

KY: So it matches very, very [well].

DE: It becomes really small, then.

KY: Yes.

DE: Those are all manual-focus...

KY: Yeah, manual focus, which they enjoy using. It's quite popular. One of the camera specialty stores in Tokyo had a stock of Leica M-to-L adapters, but it's gone out of stock because it suddenly started selling very well.

DE: Ah, because suddenly there are many fp users who want to use the Leica M lenses. That's really interesting. I could really see that. I mean, Leica people are very interested in the visual appearance of products, too. And the fp has such a nice, very high-class physical appearance to it.

KY: Yes.

DE: That's very interesting.

Followup disussion about the Sigma fp

(Here are notes from my most recent conversation with Yamaki-san, in early September 2020.)

DE: Following up on other things, we also talked about … at the time I asked you how fp sales had been going, and you said that initially there was a big spike, more than you expected, and then in March it had come down but was running to plan.

KY: Yes, the fp revived suddenly, I think in April; April, May and June, and is still selling good, but only in Japan. It’s very interesting; suddenly, starting from April, many people had to stay home and work from home, so they needed webcams.

DE: Oh yeah, of course!

KY: At that time, the fp was the only one, the only mirrorless camera, that you could use as a webcam, without installing any special software. You just plug in the USB and you can use it as a webcam.

DE: Oh, interesting! I know when I was doing a followup call with Panasonic, they said they were selling a lot of some specific models. They came out with software that let people use their cameras as webcams, but it only supported certain models. When they did that, all of a sudden, those models began selling a lot. But the fp doesn’t need any software, you just plug it in?

KY: Yes, I’m pretty sure that we triggered that trend. We did not intend to market that feature, but many of our employees used the fp as a webcam when they were working from home, so I introduced that as a use case through my own Twitter account, and it suddenly became popular, and many people bought an fp to use as a webcam, which was surprising to me.

DE: Yeah, that’s a pretty pricey webcam! But then it’s like the photographer in the family can tell their spouse or significant other “Oh, see? It’s very efficient, right? If I just buy a webcam, that’s the only thing we can use it for, but this camera we can use for a lot of things! And you want me to look good in my meetings, right?” <both laugh>

KY: Yes, many people have used that for an excuse. But sales in other countries are still low, they’re still very slow. I think the difference is that the Japanese customers are using it mainly as a still camera. But in other countries, people view it as a video camera.

DE: I wonder what the difference is culturally? I was very struck by the big video rigs it was built into at its rollout event; those really caught my eye, and I thought “yeah, it’s very compact, so it’s good for a small camera you want to put onto a car or something”. But it’s interesting that in Japan it’s very popular for still photography.

KY: Traditionally the compact, very high-end cameras are very popular in Japan. Like the Leica M camera; it’s very popular in Japan. I think Japan is the number one market for Leica, the highest sales.

DE: Oh really? Wow...

KY: Yes, and the Ricoh GR is very popular in Japan as well.

DE: Oh, that’s interesting; I don’t think it sold well at all in the US.

KY: Yeah, I know - but it’s very popular in Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Korea. So historically, we like compact format, high-end cameras.

Lenses: Sigma 24-70mm f/2.8 DG DN

Talking about lenses and L-mount in particular, you've managed to create a really impressive collection of L-mount very quickly by adapting your previous designs. I was going to ask if all of the lenses you've released so far were adaptations, but I think the 24-70mm f/2.8, that was a new design?

KY: Yes, it's designed for a short flange back.

DE: Yeah, yeah. And is that the first custom, short flange-back lens that you have done?

KY: No, we have some lenses like the 14-24mm f/2.8. We have two 14-24mm f/2.8, one for DSLR and one for mirrorless; Sony E-mount and L-mount. We [also have] 24-70mm f/2.8, 35mm f/1.2 and then 45mm f/2.8 which is bundled with the Sigma fp.

DE: So four lenses, then.

KY: Right now, yes. If I include lenses for APS-C, we have three more: 16mm f/1.4, 30mm f/1.4 and 56mm f/1.4.

DE: Yeah, and those were Sony E-mount, neh?

KY: Right.

DE: About a month after you announced the 24-70mm, you had to announce that you were overwhelmed by the orders for it. I think you said there would be a delay in getting them into the market, because preorders were very high.

KY: Very high, yes. We still cannot catch the demand.

DE: Really?! You still can't make enough of them.

KY: Yes. We've been increasing the capacity, but still we cannot catch the demand.

DE: Wow! Why do you think so popular? It is only about half the price of the Sony lens, do you think price is the big point?

KY: Yes, and also performance. It is, at least, one of the top performing lenses in this category, f/2.8 standard zoom lenses for Sony E-mount and L-mount. I believe it's the top performer, but to be fair, [I should say] it's one of the top performers. But the price is half that of the Sony 24-70mm.

DE: Yeah, yeah. So how are you able to make such high quality at such a low price? What was the secret; what's the main thing that allowed you to create it so affordably?

KY: First of all, the yield of this lens is very high. Our engineer worked very hard before he completed the optical design. While he was designing the optics, he designed the production line, and already we started the project to check the optical performance of the lens unit and align the lens unit in the assembly line. So while we were making the optical design, we also designed the assembly line, how to achieve the yield ratio.

DE: Ah. So optical and manufacturing design were sort of proceeding together. That's interesting. I imagine that you know what your tolerances are for different assembly steps, so you can do Monte Carlo simulations.

KY: Yes. And also, our designers worked very closely with the factory manufacturing engineers from the beginning. They worked together while we were developing the product on how to achieve the high yield.

DE: That seems really key. Obviously, if you have very high yield then that helps you sell for a better price.

KY: But because of that, we also invested a lot for that assembly line.

DE: Oh, a lot of special fixtures and machines and things, to help it, ah.

KY: Right. So normally, I would have to put a higher price for this lens, because we never compromise quality, and we never compromise with the materials used in that lens. So ordinarily, the price would be higher, but I gave it a little bit of a strategic price.

DE: Ah, so you did the careful development in parallel. You invested in machinery and the systems, and then you figured that if you put the price a little lower, you can sell so many more that it'd come out better.

KY: Yeah, yeah.

DE: That's very interesting. It's amazing that you're still trying to catch up! And you probably projected pretty good sales to begin with, I would think?

KY: I was not 100% confident of the sales.

DE: Ah, you were a little cautious?

KY: But once we started shipping the product, almost every week we've got very good reviews, almost all over the world.

DE: So as it got out to people, then...

KY: Then the demand continuously got higher.

APS-C lenses for L-mount?

DE: Huh, that's great; that's a nice success story. I was really intrigued when we spoke at CP+ last year, you mentioned that you expected to come out with an L-mount lens having an APS-C image circle. Can you say anything more about that at this point?

KY: Yeah. We already have three APS-C lenses for Sony E-mount, so we can make those lenses in L-mount versions. That is our current plan.

DE: Ah, I understand.

KY: But in the future, we will probably develop brand new lenses for Leica L-mount APS-C cameras.

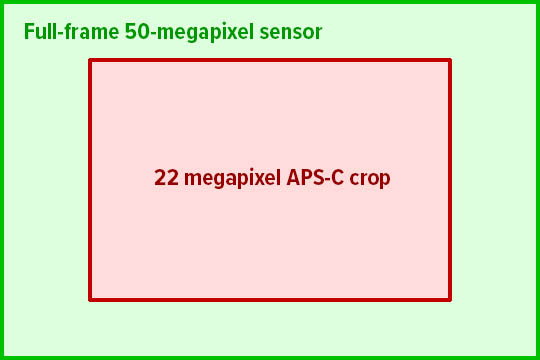

DE: I'm a little surprised to hear you say you're going to do that, because the only APS-C bodies currently are the Leica CL and TL, which I think are a very small market. Could that be a hint that there might be an L-mount Foveon camera coming at some point?

KY: No, right now we are working on the full-frame Foveon.

DE: You also made the fp with a Bayer sensor, so maybe you're thinking...

KY: Mmm. If we continue the fp concept, probably we will stay with full-frame. But this is just an assumption. We don't have such a plan right now. But just making an assumption for the future, if the sensor has large pixel numbers like 50, 60, 75 megapixels, you can take a very, very good image using APS-C with a crop mode. So in this case, you can use a very compact lens.

DE: Ahhh! That just occurred to me too.

KY: Lenses for full-frame are always bigger and heavier, so that's a challenge. If you want to use a camera with a small setup, you can have such a choice. So I think it's one of the ways to use our APS-C lenses, to make the system compact. And if you want to take a really serious photo, if you put the full-frame lens, then you can use the sensor fully.

DE: It just occurred to me that I don't know how the yield is on sensor chips, but I wonder, if you only cared about the APS-C area, would there be chips that would otherwise not be usable and you could just put the full-frame chip into the package, but restrict it to the APS-C area?

KY: If the camera is an interchangeable-lens system, you can use both, full-frame lens and APS-C. So depending on the application, people can choose.

DE: So that's more your use case, is that people would have a full-frame camera, but they might choose this as a compact lens.

KY: Yeah.

DE: Ah, hai, I understand. What's your impression about the L-mount alliance overall, in terms of how it's progressing? Do you think that as an overall system, the sales and progress have been what the partners were hoping for?

KY: I think it's too early to make such statements, or to judge the status of the project. It's still only 1.5 years since we announced the alliance and we start releasing the products. I think we need at least three years to have, relatively speakin], the complete system, even though three companies are working on the same platform. So we will be able to see the outcome from this alliance maybe...

DE: ...in another year and a half, yeah.

KY: That's right.

DE: One of the things I wanted to discuss with Panasonic is that we had a very good experience with the S1, S1R and S1H cameras, and it seems like people who had used them think very highly of them. But the problem is not many people have used them, so it's a little bit like you were saying with the fp: It needs to be out and somehow people need to become more aware of it, over time.

KY: Yeah. Actually, the S1 series is quite good. Probably, I think it's one of the best full-frame mirrorless cameras in the market today.

DE: Mmm!

KY: I think so. The shutter is great, and the viewfinder is great. Image quality is great, too.

DE: Yeah, they're very strong cameras. You said earlier that the still market is so much larger than video. Looking at Panasonic, the S1H seems like it's going to be a very significant product for them, or at least, I think it will. My sense is that the S1H is going to be driving a lot of interest in the L-mount, and pulling people into it. Leica, I would suspect, is lower volume. They've always had sort of a high-price, small-market strategy. What do you think the contributions of the various partners will be to the overall volume of sales, and the overall penetration? It feels to me like the volume sales of bodies is going to be more up to you and Panasonic rather than Leica.

KY: Yeah, sure. Because the price of Leica cameras and lenses is quite high, the user base is quite limited. So in terms of the volume, Sigma and Panasonic can contribute more to the alliance. But first of all, Leica is the licensor of the L-mount. And also Leica is a high premium brand, so having Leica in our alliance means a lot.

DE: Yes, you get kind of a halo effect from Leica sort of elevates the whole L-mount perception.

KY: And also I personally believe it's very good for Leica users. Having a whole system just with Leica products, it costs very much: Cameras, lenses, accessories, everything. Even for very rich people, it costs too much.

DE: Yeah, a camera and one lens is $10,000. And then you want another lens, it's another $5,000-6,000.

KY: Yeah. So they may like to try a Sigma lens on a Leica camera. I think having more choice is very good for Leica users.

DE: Yeah, I think I would agree with that. I think a lot of people like Leica, but it’s unapproachable for them. They would want to have an assortment of lenses, but you can't afford to do that with Leica unless you're very wealthy. Now, they could buy a Leica body and lens, but they could also have other options for lenses from you and Panasonic.

KY: Yes. Yep.

DE: Not that we ever could, but it would be interesting to know how this has affected the sales of Leica bodies. I would think that over time it would help it, as you said.

KY: Actually, I heard that the Leica SL2 is selling quite well. I don't know the number, but I heard that they...

DE: ...it's being a very good product for them on volume?

KY: Yeah, yeah.

DE: I'm curious about the sales in general of your mount converters, and the mount conversion service. As there have gotten to be more and more mirrorless cameras, are you selling more and more adapters?

KY: Our adapters are still selling very well. The sales are becoming a little bit lower than during the peak time, but still we are selling good numbers. Mainly the adapter from Canon EF to Sony E-mount.

DE: And you have a mount conversion service also. Have people been taking advantage of that, or are they more just using adapters?

KY: We regularly receive requests for mount conversion service every month, but it's not a huge number. But I clearly see that some people like to switch from Canon EF or Nikon F-mount to Sony E-mount. And also some users have already changed from Canon to L-mount, or even Sigma SA-mount to L-mount.

DE: Really? Wow. I suspect it's one of those things where it's an important statement to people that you have that available, but it's probably not a big volume item, so it's strategic, I think.

KY: Yeah.

Why so much FLD and SLD glass in the 24-70mm?

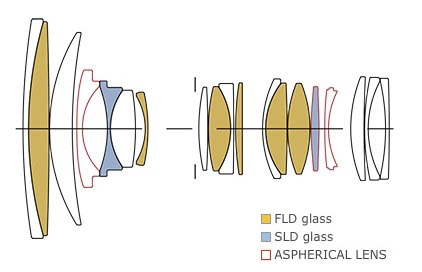

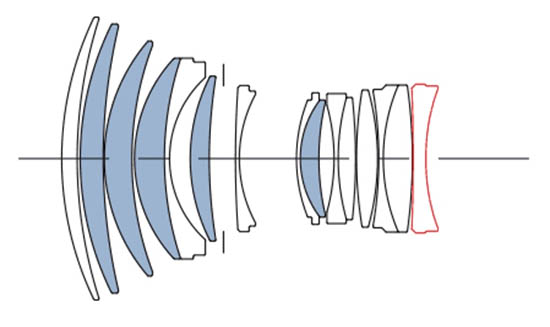

DE: This next question is going back to the 24-70mm. I was wondering about what made it so affordable, which you answered about the manufacturing. But I was struck, when looking at the optical formula, by how much FLD and SLD glass there is in there. Did that contribute to the manufacturability, or was that more just to increase the image quality?

KY: Just to increase the image quality. Actually, polishing FLD/SLD glass is quite costly, and also, yield is very low compared to traditional glass.

DE: Ah, I was curious about that.

KY: Because the exotic glass is quite soft compared to the traditional, so it's easy to create a scratch when you are polishing the glass.

DE: Ah, interesting.

KY: There are three steps to polish the glass. The first one is called lap grinding, or we call it curve generation. The second is smoothing, and then the final step is polishing. But in the case of FLD/SLD, we need to polish those lenses two times, or sometimes three or four times to remove all the scratches.

DE: Really? That's interesting. Wow.

KY: The polishing step is very fine polishing; we use a very fine tool.

DE: Yeah, I think it's called rouge; it's cerium oxide or something, I think. I know jeweler's rouge is a very, very fine abrasive, yeah.

KY: Yes. But if we polish the FLD/SLD, we use even finer materials to polish the glass.

DE: Oh really?

KY: Normally, if we polish traditional glass, each side is polished once per side. But SLD/FLD are three times on one side, and three times on the other, so six times polishing. It's quite costly.

DE: Wow! Wow. And so it's three successive stages: Fine, extra fine, super fine.

KY: Right.

DE: Wow. I had understood that they were more difficult to work with, but didn’t know why, or just how much had to be added to the process to accommodate them. You answered one of the questions I had, before I asked it :-)

KY: So optically, the scratches are OK. But visually, it's not great. Because if we see the glass like this, you can see some very fine scratches on the surface. So we need to remove all such scratches.

Developing new optical glasses

DE: Ah, that's interesting, too: It's not really an optical problem, because the scratches are such a tiny, tiny part of the overall surface. But it wouldn't look good to users if they look in a lens and see scratches. Interesting. For SLD -- and I assume it was the same with ELD and FLD -- you developed those in a joint venture partnership with a glass manufacturer, I think?

KY: Actually, it's not a joint venture. We buy the glass from Hoya and Ohara, which are already big companies, but we have a very informal project together. We have regular meetings between our optical engineers and their engineers, and they ask what kind of material we need.

And sometimes they make a prototype, and we do test polishing at our factory. Then if we find it's good, we will use it. So that's the reason why we always have the priority; why we use new glass before other companies. Actually, it's quite risky to use this new glass. If it has a very low yield in the polishing process, you can add greatly to the cost. Also, you cannot achieve the production plan. So it's quite risky, and nobody wants to take that kind of risk.

So all major companies watch how other companies are doing. And normally, Sigma is the first one to use it. And then, after they see Sigma use that glass, then they start using the glass.

DE: And so at that point, it's a glass that Hoya or... You said it was Ohara?

KY: Yes. Ohara is a subsidiary of Canon.

DE: Ahhh, hai. So at that point, it's a glass that's in the catalog for Hoya or Ohara. And so other companies can buy it, but they kind of let you take the risk initially.

KY: Yep.

DE: I never really knew what the limitations were on the glass formulation. I know some of it has to do with whether things will precipitate out of the glass, and then they get defects. I know that if they try to put too much of certain elements into the glass, they can get little precipitates as it cools, like it crystallizes a little, I think. It's like the added elements want to come out of solution in the glass, so they'll get little crystals or precipitates inside the glass. So I've been aware of that as a limitation. But I hadn't realized that there could be that much difference in polishing properties between glass. So Hoya might come to you with a glass and say "Hey, here's this extra-low dispersion you asked for", but then you take it to the factory and try polishing, and it's like, "No, we can't polish this."

KY: Yeah! Sometimes, yes.

DE: Huh. Interesting.

KY: I'm not sure if I understand correctly, but when, let's say, Hoya tries to develop a new glass and it's not successful, there are several reasons. First of all, the quality is not stable; every lot has slightly different characteristics.

DE: Oh, too much variation, and they can't control it closely, yeah.

KY: Too much variation. In this case, they cannot move to mass-production. Also, the characteristics are too exotic... Maybe it’s too soft, and for the manufacturer it's difficult to polish the glass. That's one example. So regarding evaluation, it's a problem for the glass supplier, because the cost could be very high. And for us, we cannot guarantee certain characteristics if there is too much variation.

DE: Yeah, yeah. It's very interesting to me. A couple of years ago, I went on a tour of Nikon's Hikari glassworks in Akita, Japan, and it was fascinating to me. I didn't realize that they can actually adjust the refractive index by annealing the lens blanks. So the glass comes out of the melt, and is being cast, and the refractive index starts out low. Then as they anneal it, the glass gets more dense and the refractive index actually goes up. So they might have a certain amount of variation in refractive index coming out of the melt, but then they measure it, and it's like "OK, this needs to anneal for 20 hours. This one needs to anneal for 15 hours," or whatever.

KY: Yes, yes. So Ohara, the subsidiary of Canon, they anneal the glass twice. They call it double-casting. Because of that technique, they say they can stabilize the quality.

DE: Oh, interesting.

KY: Hoya always uses single-casting, but Hoya claims that they can stabilize the quality because of advanced technology.

DE: Ah!

KY: So I don't know...

DE: ...which to believe or what the story is.

KY: Yeah. But it's true that Ohara clearly said that they anneal twice to make an even, very uniform quality of glass.

DE: That sounds like what Nikon's doing, because it's cast, and it has to be annealed to relieve stresses. But that's the point, then, that they test the refractive index and then it gets annealed a second time not to relieve stress, but to change the refractive index.

KY: Ah! I see.

DE: Yeah, that was very interesting. I asked what it is about annealing it that changes the refractive index, and they said it actually becomes slightly more dense, that the disordered clusters of molecules will kind of relax into a tighter configuration.

KY: Interesting.

DE: Yeah, fascinating, neh? So Ohara will come to you, or Hoya will come to you, and say "Here's a new glass we have, what do you think?" Or you would be asking them first, and saying, we'd like...

KY: Both ways. But it's not clear which one makes the proposal suggestion first, because we have regular meetings, and always the engineers give their requests, and then Hoya or Ohara propose a new material. So it's not clear who [first makes a proposal].

DE: It's chicken or egg; it's always back and forth. Huh. And FLD is supposed to mimic fluorite; fluorite is very low dispersion, but it's also anomalous dispersion, right? In some parts of the spectrum, the dispersion is opposite to regular glass.

KY: I'm pretty sure that the FLD has almost the same characteristic as fluorite. Because we have studied several times if we should use fluorite, because many people said fluorite is good. But after many studies, we concluded that there is no reason to use fluorite because the cost is high, but the character is the same.

DE: Yeah.

KY: So if we used fluorite, probably it would just be for the marketing purpose. We could not tell the difference between fluorite and] FLD in terms of the optical performance.

DE: Really? Wow. And fluorite is even harder to handle; it's very, very soft I think, neh?

KY: Yeah, yeah.

DE: And the materials are expensive, as well.

KY: Very expensive.

Followup: Lots of stock for the 24-70mm f/2.8 now

DE: And at the time too, talking about the 24-70mm DG DN lens, you said that you still couldn’t catch up to demand. How are you doing now, have you finally managed to catch the demand?

KY: Yes, fortunately or unfortunately, our sales dropped dramatically in April and May, but in order to protect the employees’ income, we didn’t stop the production in April. We slowed down production, but we did not stop it. So during this time, we piled up inventory of the 24-70mm. As a result, right now, we don’t have any delivery issues.

DE: That’s great, that you could do that for your employees; you’re very loyal to them, that’s something I’ve always admired about you and Sigma.

KY: Yes, they are an asset for us(!) [Ed. note: Yamaki-san said this with considerable feeling. He genuinely believes that Sigma’s employees are the core of their business success. My sense has always been that the employees have a similar sense of loyalty to him and Sigma in return.]

DE: Are there any other of your new lenses that have been more popular than you expected?

KY: The macro lenses were surprising. In the US, for the period from April to June, the sales of our macro lenses increased by 75% compared to last year. The macro lenses have been very popular during this period. Also, in APS-C, the 16mm f/1.4 is

very popular. I think that many people use it for broadcasting or YouTube broadcasting. The people who use cameras like a Sony 6000 series or Panasonic GH series; the so-called YouTubers use that sort of camera; I think many of them like this lens.

DE: Wow, that’s very wide, although I guess on APS-C...

KY: Yes, it’s equivalent to a 24mm on full-frame.

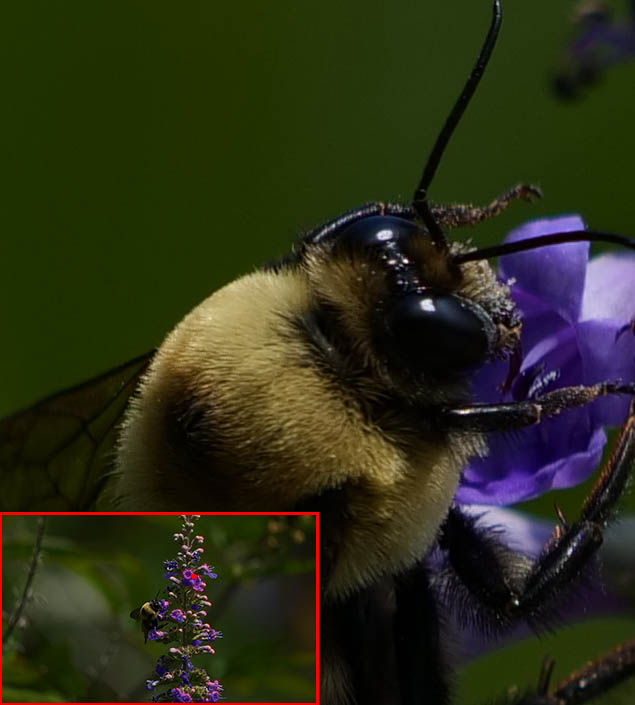

Followup: Why/how is the new Sigma 56mm f/1.4 DC DN so sharp & so low-priced?

DE: I was looking over your recent lens announcements since we last spoke, and was very impressed. They all look very good, but the one that amazed me was the 56mm f/1.4 DC DN, it’s just so sharp; looking at the MTF curves, they’re just very, very high! I mean I guess APS-C sensors are smaller, so 30 lines/mm there is more like 20 lines/mm on a full-frame (relative to the total frame size), but still, I was very surprised by the optical quality, especially for such an affordable price. Was there anything in particular that the engineers did to achieve that combination of price and quality?

KY: Hmm. First of all, this 56mm f/1.4 is one of the f/1.4 series of lenses for APS-C size cameras. I mentioned the 16mm f/1.4, plus there’s the 30mm f/1.4, and now there’s the 56mm f/1.4. These are the “three brothers” of lenses for APS-C size sensor cameras. So these are 24, 45, and 85mm equivalents. We first released the 30mm f/1.4 and then the 16mm; both lenses are well accepted for their optical performance and compact size and affordable price. They are some of the best selling items at Sigma today. The 56mm was the last, so we decided to keep the same concept of compact, lightweight and high optical performance. We gave that concept to the optical engineers, so I think that optically they did a great job.

DE: Yeah, yeah; it’s selling in the US for $450, which seems like an amazing price for that level of optical quality.

KY: The price is a bit strategic, because the price of the APS-C sized camera bodies are very low. So from the customer’s point of view, the lenses for the APS-C bodies should be priced low too. So we set the price strategically for those three lenses.

DE: It’s strategic, in the same sense that the price on the 24-70mm is. I recall you telling me that you deliberately set the price on that one lower than you ordinarily would, hoping that the volume would make up for it. - And it looks like that was a very smart move, given how huge the demand has been for that lens.

KY: Yes, because we ... as you know, we make almost all the component parts for our lenses at our Aizu factory. So keeping on running the factory [at full production] is most important. Even if we sacrifice our profit margin a little bit, keeping the factory running is actually providing more profit to us. If Sigma was a company like other big companies who purchase many of the component parts from other suppliers, we probably couldn’t do that. Maybe we would have to set the price higher than we did for this one. We sacrificed our profit margin, but we prioritized keeping the factory running.

DE: Right, which it seems to me is actually working out very well for you. If the price of the 24-70mm had been 40-50% higher than it is, it wouldn’t have gotten anywhere near the same level of attention. If it had been a $1,500 lens, people might have said “oh, that’s interesting, it seems like a reasonable deal, I’ll have to check it out.” But at $1,100 (in the US), it’s like “holy mackerel, I’ve gotta get one of those!”

I guess for other manufacturers, if they’re buying a part and it’s like ¥1,000 for 100 of them, if they buy 200, maybe the price only goes down to ¥980. But for Sigma, the factory is there, so as long as you keep using it, the price keeps coming down.

KY: Yeah, so if [another company] is purchasing the parts, it’s a variable cost, right? They can’t reduce that price, but because we have our own factory, that’s a fixed cost. So as long as we increase the efficiency, the cost per unit will decrease. So keeping the factory running at high efficiency is very important.

Followup: Lots of SLD glass in the Sigma 85mm f/1.4 DG DN; why?

DE: Yes, very interesting! I was also really amazed by the 85mm f/1.4 DG DN; that looks like an incredible lens. I’m noticing how different the optical formulas are these days; the 24-70mm that we talked about last time has a lot of FLD glass in it, and I see that the 85mm has I dunno, five or six SLD elements, so it seems like there’s a lot of special glass in these new designs. Last time we spoke, you told me that FLD was actually much more difficult to work with than conventional glass, requiring 3 polishing steps vs just one. How about the SLD, is it similar or is it more like conventional glass that way?

KY: We use so much SLD and FLD simply because it helps to improve the optical performance. Using such exotic, expensive material helps a lot with that. It requires very careful attention to take care of the glass, and also requires additional polishing processes. So the manufacturing costs of those glasses are very high.

DE: I know you said that with FLD you have to polish it three times. Is SLD similar that way?

KY: Basically yes, they are similar, and depending on the glass shape or the diameter of the element we may stick to just one polishing process, but basically it requires additional processing.

DE: Is the glass itself significantly more expensive than conventional glass? Is the bill of materials a significant part of the finished product cost?

KY: Yes, the glass is more expensive, but also the manufacturing cost is much more as well.

DE: Yeah, I’d think that the manufacturing cost would be the biggest component. When you look at all the costs associated with making a lens, I wouldn’t think that raw materials are that large a component.

KY: Correct, yes.

Followup: Comments on the new Sigma 100-400mm f/5 - 6.3 DG DN

DE: Looking at the new 100-400mm, Dave Pardue from IR just did a video review of the new Panasonic S5, and shot quite a bit with the Sigma 100-400mm DG DN as part of that, and he was very impressed. What was surprising to us is how sharp that lens is at the tele end. We’re accustomed to zooms being sharper at the wide end, but as you move towards tele, they tend to get softer and softer. The new 100-400 seemed to stay very sharp all the way to its maximum focal length. It’s also very compact; we were surprised that you managed to make a full-frame 100-400 so small. Is there anything in particular that the lens designers did to accomplish this?

KY: Of course, our optical designer and mechanical designer did a great job to make such a fantastic lens, but [there was] nothing special in terms of technique to achieve such a high performance. One thing I can tell you is that we’ve been working so hard to strengthen our manufacturing capabilities. Not in terms of volume, but also the quality. In recent years, we have invested a lot to make much higher-precision parts and we’ve invested a lot to be able to assemble those parts into the lens barrel with much tighter tolerances. So I think that kind of … so many years of work have resulted in such a product.

DE: Ah, I wonder if part of the story might be that your greatly-improved manufacturing processes and tolerances have given your engineers more leeway in terms of the lens designs? I’ve heard lens designers from various companies talk in the past about sometimes needing to dial back some aspects of a design, just so it can be manufactured efficiently. The logical conclusion from those comments is that if the factories were able to hold tighter tolerances, the designers would have been able to come up with higher-performing optical designs.

KY: Even if you design very good lenses, if the manufacturing capability is low, you have to set the outgoing criteria quite low. Right now, we can set the inspection criteria for outgoing shipments very high, very close to the design spec. That’s the reason why many customers enjoy the good quality [of our] products.

DE: As I said, maybe it gives the designers more flexibility, so they’re not being constrained as much by what the factory can manufacture?

KY: Yeah, yeah.

Followup: What's up with Diffractive vs Geometric MTF curves?

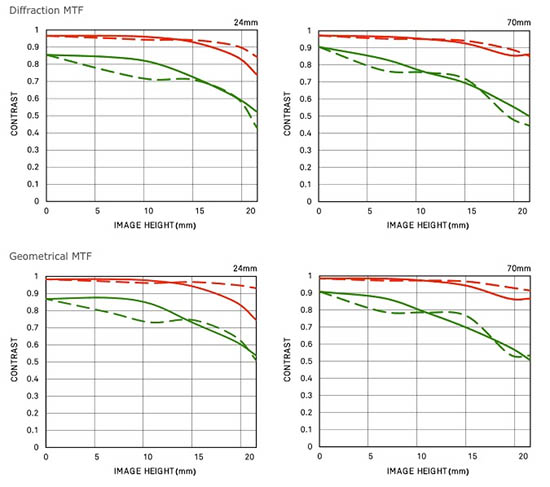

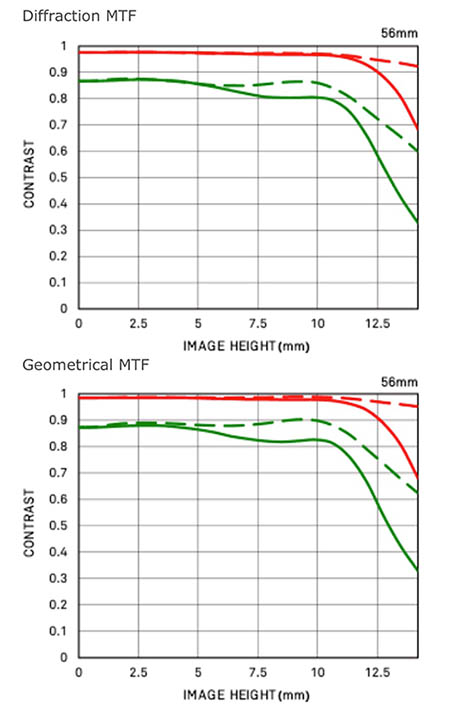

DE: I had one very general question about MTF curves, because as I was looking at the performance data on your site, I see that you publish two different sets of curves; one called “Diffractive” and the other “Geometric”. I understand the difference between them, but wonder why you publish both. Do other manufacturers only show geometric, is that the reason, so your curves will be equivalent to theirs, or is there another reason?

KY: Actually, we don’t know [what other companies are doing]. That’s the reason why we publish the two types of MTF curves. Some particular lenses can show an MTF curve that’s much better in geometric than diffraction. So if the other company is publishing a geometric MTF curve for one of their lenses, and we publish a diffraction MTF curve for ours, it may confuse the customer. So we decided to publish both.

DE: So Company “B” may publish an MTF curve that a user would look at and say “wow, that’s a great MTF plot”, but they might be using a different standard. I think on your website, it says that the geometric curves are very easy to generate…

KY: It makes the lens look good.

DE: Ah, so it’s not necessarily that they’re easier to generate, just that they make lenses look better than they would be in actual practice. So by publishing both types of curves, it at least opens the question in people’s minds of what sort of curve the competitors are posting.

KY: Yes.

Editor's explanation: Most of our readers are familiar with MTF curves showing lens performance. The graphs usually have two sets of lines on them, one corresponding to the maximum contrast for a black and white line target, typically imaged at pitches of 10 lines/mm and 30 lines/mm on the sensor's surface. The 10 line/mm curve corresponds to general lens contrast, while the finer-pitched one is an indication of the lens' resolving power.

Contrary to what most people might expect, these curves don't represent the measured performance of any particular lens, but rather are calculated by computer based on the lens configuration. There are two ways the curves can be calculated though, one purely based on the geometry of the lens elements, the other taking diffraction into account.

We're all familiar with the effects of diffraction; it's the reason images shot at f/22 or other small apertures are so soft. We tend to not think of diffraction happening at large apertures, but it's an optical phenomena that's always present.

It turns out that diffraction can have a significant impact on lens performance even at maximum aperture. The extent of the effect depends a lot on the internal structure of the lens, so there's no simple way to extrapolate from MTF curves calculated purely on the basis of the lens geometry to the actual lens performance including the effects of diffraction. With the obvious exception of diffractive optics, that depend on diffraction to focus the light, diffraction always reduces lens performance, reducing both contrast and resolution.

Of course, actual lens performance always includes the effects of diffraction, so MTF curves including that effect are a lot more relevant to real-world picture taking.

The problem is, the vast majority of lens makers don't say whether their MTF

How is the industry looking?

DE: I think I'm down to my last questions. What's your personal projection for how the photo industry is looking? I mean, I guess I'm asking you what it would've been before the coronavirus; I guess who knows now? But 2019 was a big drop. I think people had been expecting it to go slowly, and overall sales dropped suddenly. Did it look like it was leveling off again?

KY: I guess the market would shrink in 2020, even if we didn't have coronavirus. Probably the coronavirus issue will escalate the problem. Without coronavirus, I assumed that the market would shrink but probably toward the end of this year to next year, I expected it to hit the bottom, and then level out.

Last year, the quantity of interchangeable-lens system cameras sold in the market was 8.5 million units. But actually, the peak time was 17 million units. So last year was about half. But before digital cameras, film SLR sold about four million to five million units. So it was originally a very small market. So I think it was kind of a boom economy starting from mid-2000 to the beginning of 2010, and then it's going down to the normal level.

DE: Mmm-hmm.

KY: I think probably five to six million is a good number to be stable. Thanks to smartphones, more people are interested in taking better pictures, and some of those people would like to buy high-end cameras. So probably, I think the market size for digital interchangeable-lens system cameras would be higher than for film SLRs. And also because the learning cost is very low compared to the film camera.DE: Oh, yeah, much lower costs than film, that's a good point. Because now, you can see your picture right away. I remember I would shoot a 36-exposure roll, and sometimes none would come out.

KY: *laughs*

DE: I think that's a good point. Yeah, and the steady state in the film era, too, part of it was the very long practical product lives. You know, you'd shoot with the same camera for ten years or whatever. One thing that drove so much volume with digital was as we were going up the technology curve, people were buying new all the time. But now my feeling is we're coming back to more like a five-year cycle maybe, for people getting cameras.

KY: Mmm.

DE: But that's good. So maybe another year of some decline, but then leveling out, once the coronavirus is dealt with.

DE: That's actually all my questions, it's been really interesting as always! I always start with a few questions, and then once we begin, you tell me things that I ask more questions about. I always enjoy it very much. Thank you as always!

KY: Thank you, too.

Summary

Wow, there's a lot to unpack here! I'll try to hit the high points briefly.

On the COVID front, Sigma's production has been almost entirely unaffected, thanks in large part to the extent to which they're vertically integrated, making most of the component parts for their lenses in-house. Their factory's location in a mountain basin in northern Japan also helps, as that area has remained almost entirely unaffected by the virus.

Turning to products, I began with the Foveon sensor and the undoubtedly difficult decision to postpone a full-frame Foveon-based camera to some as-yet-unknown time in the future. The decision was driven by two factors: 1) There were some design errors in the then-current full-frame sensor, and 2) They've changed to a new foundry partner for fabricating the sensor chips. While there's no set schedule for when the full-frame chip will be available, it sounds like good news that they now have a foundry partner located practically next door (globally speaking, at least) to the Foveon engineering team.

Sigma's groundbreaking, super-compact fp full-frame L-mount camera seems to be doing extremely well in Japan, and performing to plan overall. Interestingly, a lot of Japanese sales seem to be driven by Leica shooters using M-mount lenses on it via Leica's M-mount to L-mount adapter.

Yamaki-san also said that he views the fp as being as much for still shooters as for videographers. In my own mind I'd seen it as more for video users, but it seems that's more of a Western take on it; the vast majority of users in Japan are still photographers.

We talked about Sigma's latest lens announcements, both in our initial conversation and in the followup just a few days ago. I've said before that this is the Golden Age of lens design, and there has been no better time in history to be a photographer. Sigma's offerings over the last few years have been evidence of this, and especially some of their latest announcements.

Their new 24-70mm f/2.8 DG DN (DG means it's a full-frame lens, DN means it's "Designed New" for mirrorless mounts) is a stellar example: It's just remarkably good, possibly the best 24-70/2.8 on the market, and at half the cost of the competing Sony model (for example). Some of this is thanks to the extensive use of "FLD" (Flouride-like) optical glass, and the pricing is thanks to both the design process itself and a strategic decision by Yamaki-san. On the design front, the engineer responsible worked closely with Sigma's manufacturing staff to develop new ways to insure maximum optical quality that was also manufacturable. For Yamaki-san's part, he decided to both invest heavily in production fixturing for manufacturing the lens, as well as to price it "strategically". This last means means he set an aggressive price point that would require high sales to justify. As it's turned out, this was a very savvy decision, because demand for the lens has been off the charts, far exceeding expectations and requiring Sigma to work hard to keep up with demand for it. This is great for photographers, because it means we have an unusually high-quality 24-70mm/2.8 zoom at an unbeatable price.

One surprise for me in the conversation was when Yamaki-san said that he was planning to develop L-mount lenses with APS-C image circles. This seemed odd, given that there aren't currently any L-mount models with APS-C sensors. Yamaki-san explained that lenses with APS-C coverage would be much more compact than full-frame ones, and with high-resolution sensors, even an APS-C crop would be useful, making for a very compact rig with ample resolution. That argument makes some sense, but looking at Nikon's Z50 as an example of a new APS-C camera using a mount that's otherwise associated with full-frame cameras, it wouldn't be a stretch to imagine L-mount alliance partners releasing bodies with APS-C sensors in them.

We then turned back to lens technology, and specifically the 24-70mm and the extraordinary amount of FLD glass it uses (no less than 6 of its elements are made from FLD glass). I wondered if perhaps the benefits of FLD glass might have helped improve manufacturability, but it seems that the opposite was the case. The decision to use that much FLD glass was purely down to optical performance, as it turns out that FLD glass is much more difficult to manufacture lens elements from. The problem is that it's a very soft material, so is exceptionally prone to scratching. Lens elements made from ordinary optical glass require just a single polishing operation, once the basic shape of the lens has been established. By contrast, FLD glass requires three separate polishing operations (which of course have to be done separately for each side of the lens), progressing through fine, finer and super-fine grit sizes to deliver the same finish. So it takes three times as long to polish an FLD optical element than one made of conventional material. Even with this added manufacturing difficulty, though, Sigma's strong investment in production-line fixturing and testing still lets them sell the new 24-70mm f/2.8 DG DN for less than the competition.

We also talked a bit about optical glass, and the relationship between Sigma and its glass suppliers. I'd always thought of optical glass makers as just brewing up new glass formulations and offering them to lens makers. In fact (probably no surprise), there's a tremendous amount of ongoing collaboration between Sigma and its glass suppliers. As a smaller, closely-held company, Sigma is more able (or at least more willing) to take risks on new optical glass formulas, giving them an advantage in their advanced lens designs over larger competitors.

In my followup questions, I circled around to some of the new lenses that Sigma's announced in the time since my visit, which are characterized by very high performance for their price points. I had the same general question about all of them: Their performance is in many cases is so good that I assumed the engineers must have had some tricks up their sleeves to achieve them. It turns out though that there was nothing particularly unusual, or at least no fundamentally enabling technologies involved in any of them, just very good engineering.

I do think that two factors are at play, though. First, Sigma has made huge and ongoing investments in their manufacturing technology and fixturing, so they're able to maintain a much higher level of precision when it comes to fabricating these new optics. This both insures performance much closer to the design goals (helped by Sigma's 100% optical testing of them using in-house developed test systems) but also gives the optical engineers more flexibility in their design work. This is because the designers can push the envelope more, vs having to accept compromises for the sake of manufacturability.

The second factor is that I see a lot of advanced glass (FLD and SLD) being used in many of these new designs. Sigma's engineers work very closely with their optical glass suppliers, to develop new formulations with enhanced characteristics. Yamaki-san explained to me that there's risk associated with building new, advanced glass formulations into lenses, and as a smaller company with more focused decision-making, Sigma is more willing to assume those risks than some of their larger competitors.

I also got some clarity on what the difference is between geometric and diffractive MTF curves, and why Sigma has begun publishing both types for their lenses. Calculated MTF curves based solely on the lens elements' geometry make some lenses look better, but depending on the specifics of each lens design, they may or may not accurately predict real-world performance. Sigma doesn't know whether or not competitors' MTF curves are calculated to include the effects of diffraction, so they've begun publishing both types of curves, so consumers can get a more accurate impression of how the lenses will perform in use, and compare against competitors on an equal basis.

Finally, Yamaki-san's projection for the long-term health of the interchangeable-lens photo market is what I'd call cautiously optimistic. He points to historical levels of film-SLR sales of about 4-5 million units back in the day, and thinks that the market will level out at about 5-6 million units in the digital era. ILC bodies sold 8.5 million units in 2019, so there's still a little ways to go before it levels out, but his assessment agrees with mine, namely that the core photo-enthusiast market will remain stable over the long haul.

As always, it was a fascinating discussion (two separate discussions, actually) with Yamaki-san. As the ultimate authority for all things Sigma, he has an unusual ability and willingness to speak frankly about Sigma's products, plans and technology. Thanks to him as always for not only making time for my many questions, but also for his characteristically forthright answers!

What do you think? Please leave your comments and questions below, and I'll make a point of monitoring the thread and answering any questions I'm able to, over the next couple of weeks after posting.